Module 01

Hashima in Time and Place

Industrial island, imperial labor, contested memory

Overview

- Hashima's compressed geography — engineered through landfill and seawalls — made it a technology of labor concentration and corporate governance

- The island's story spans Meiji industrialization (1890s), wartime mobilization (1939–1945), postwar community (1945–1974), and heritage-making (2015–present)

- Japan's 2015 UNESCO commitment to present the "full history" remains unfulfilled, with the Industrial Heritage Information Center prioritizing celebratory narratives

- The dominant "ruin aesthetic" pulls attention toward photogenic decay while allowing the 1940s to recede from view

Hashima: A Timeline

Industrial Foundation

Mitsubishi acquires mining rights and transforms a small rocky outcrop into an integrated industrial ecology through landfill, seawalls, and vertical construction.

- 1890: Mitsubishi acquires Hashima mining rights

- 1916: Japan's first reinforced concrete high-rise apartment built

- 1930s: Island density intensifies as coal production scales

Wartime Labor Mobilization

Coal becomes a strategic war resource. Japan expands legal mechanisms for directing labor to mines, including mobilization of Korean and Chinese workers under coercive conditions.

- 1939: National labor mobilization laws enacted

- 1940s: Korean and Chinese workers brought to Hashima

- 1945: War ends; contested histories of this period remain central to contemporary disputes

Peak Community

Under transformed political conditions, Hashima continues as an operating mine. Population peaks at over 5,000 people—the highest population density ever recorded globally.

- 1950s: Schools, medical facilities, and amenities serve dense community

- 1959: Population peaks at approximately 5,259 residents

- This era generates the archive of "everyday life" images that later dominate nostalgia narratives

Decline and Abandonment

Japan's energy transition from coal to petroleum makes the mine economically unviable. Mitsubishi closes operations and residents depart rapidly, leaving behind an accidental archive.

- 1960s: Petroleum displaces coal; economics shift

- Jan 1974: Mitsubishi closes the mine

- Apr 1974: Last residents depart; island sealed

Ruin Aesthetics

Decades of salt corrosion and typhoons transform Hashima into a modern ruin. "Battleship Island" enters popular culture through photography, film, and tourism interest.

- 1974–2000s: Decay creates photogenic ruins

- 2009: Island reopens to limited tourism

- Ruin aesthetic pulls attention toward 1950s/1970s, allowing 1940s to recede

UNESCO Inscription & Contested Memory

World Heritage listing formalizes international dispute. Japan commits to presenting the "full history" including coerced labor—a commitment UNESCO monitors as ongoing compliance.

- 2015: UNESCO inscription; Japan acknowledges workers "brought against their will"

- 2020: Industrial Heritage Information Centre opens in Tokyo

- 2021: UNESCO expresses "strong regret" over unfulfilled commitments

- Ongoing: Interpretive governance remains contested

Hashima Island—a coal mining facility off the coast of Nagasaki—sits at the centre of an unresolved dispute over how Japan commemorates sites where Korean and Chinese labourers were forced to work during World War II. The site was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2015 as part of Japan's "Sites of Japan's Meiji Industrial Revolution" after Japan acknowledged that "a large number of Koreans and others" were "brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions" at multiple component sites including Hashima (UNESCO World Heritage Committee 2015, 2021). Subsequent interpretive practice, particularly at the Tokyo-based Industrial Heritage Information Center, has remained contested, and UNESCO has repeatedly found Japan's response inadequate (UNESCO World Heritage Committee 2021; Dionisio 2023; Johnsen 2021).

Hashima (Gunkanjima) is small enough to be grasped in a single glance, yet historically large enough to condense a century of industrial capitalism, imperial expansion, wartime mobilization, postwar prosperity, and postindustrial decline into a few engineered hectares. That compression is not merely geographic. It is administrative and interpretive. Because the island was expanded by landfill, protected by seawalls, and governed as a Mitsubishi company town, its built environment functioned as a technology of concentration that organized labor, housing, provisioning, and social life within hard boundaries. Those same constraints make Hashima unusually susceptible to selective representation. The island's story can be told as engineering triumph, as community, or as photogenic ruin, each of which is partly true, and each of which can be narrated in ways that either foreground or displace coercion, hierarchy, and responsibility.

Scholarly Context: Procedural Governance and Memory Conflicts

This matters for the larger project because immersive media does not enter a neutral historical field. It enters a governance environment already shaped by heritage nomination practices, international monitoring, rights regimes, partnership conditions, and reputational-risk framing. One way to see this, without making our case study into a commentary on UNESCO procedure as such, is through the work of Jihon Kim and Andrew Gordon, who show that East Asian "memory conflicts" at UNESCO increasingly hinge on procedural architectures and institutional forums, not only on competing historical claims. In their account, states and their advocates learn to shift contests over colonial and wartime pasts into questions of who may nominate, how objections are handled, and how "dialogue" becomes a durable mechanism for deferral and containment, including within UNESCO's Memory of the World program (Kim and Gordon 2025).

Their second key observation, equally relevant here, is that shifts in diplomatic tone do not necessarily signal interpretive change, a point that clarifies why local heritage actors can treat "controversy" as a standing risk even when international language temporarily softens (Kim and Gordon 2025). In other words, procedural time and institutional risk are not backdrops. They are active historical conditions of speakability.

1. An Industrial Island (1880s–1945)

Coal extraction around Hashima predates the island's most famous concrete skyline, but early operations were vulnerable to the sea and to logistical fragility. The decisive pivot was corporate consolidation. In 1890 Mitsubishi acquired mining rights and began scaling production by treating Hashima as an integrated industrial ecology: the mine, the docks, the seawalls, and the housing were components of a single system designed to stabilize output under marine constraint. The island's land itself was manufactured through landfill and maintained through protective infrastructure, so "place" here was not simply inherited geography but engineered capacity.

Two spatial facts structured everyday governance. First, the seawalls did more than keep water out. They made life depend on regulated maritime transport for food, supplies, and personnel, and they fixed the island's perimeter as both protection and containment. Second, the island could not expand horizontally in response to workforce growth. It grew vertically. Hashima's reinforced-concrete apartment blocks, including the 1916 high-rise often cited as a landmark of early Japanese high-rise construction, were not built primarily as monuments to modernity. They were built as a pragmatic solution to labor concentration, a way to warehouse and reproduce a workforce on minimal ground. By the mid-twentieth century the island's density was globally striking, but density should be read as a governance condition. Where bodies are concentrated, circulation is routinized, and the boundary between "work" and "life" is thin, corporate authority can operate through infrastructure as much as through explicit rules.

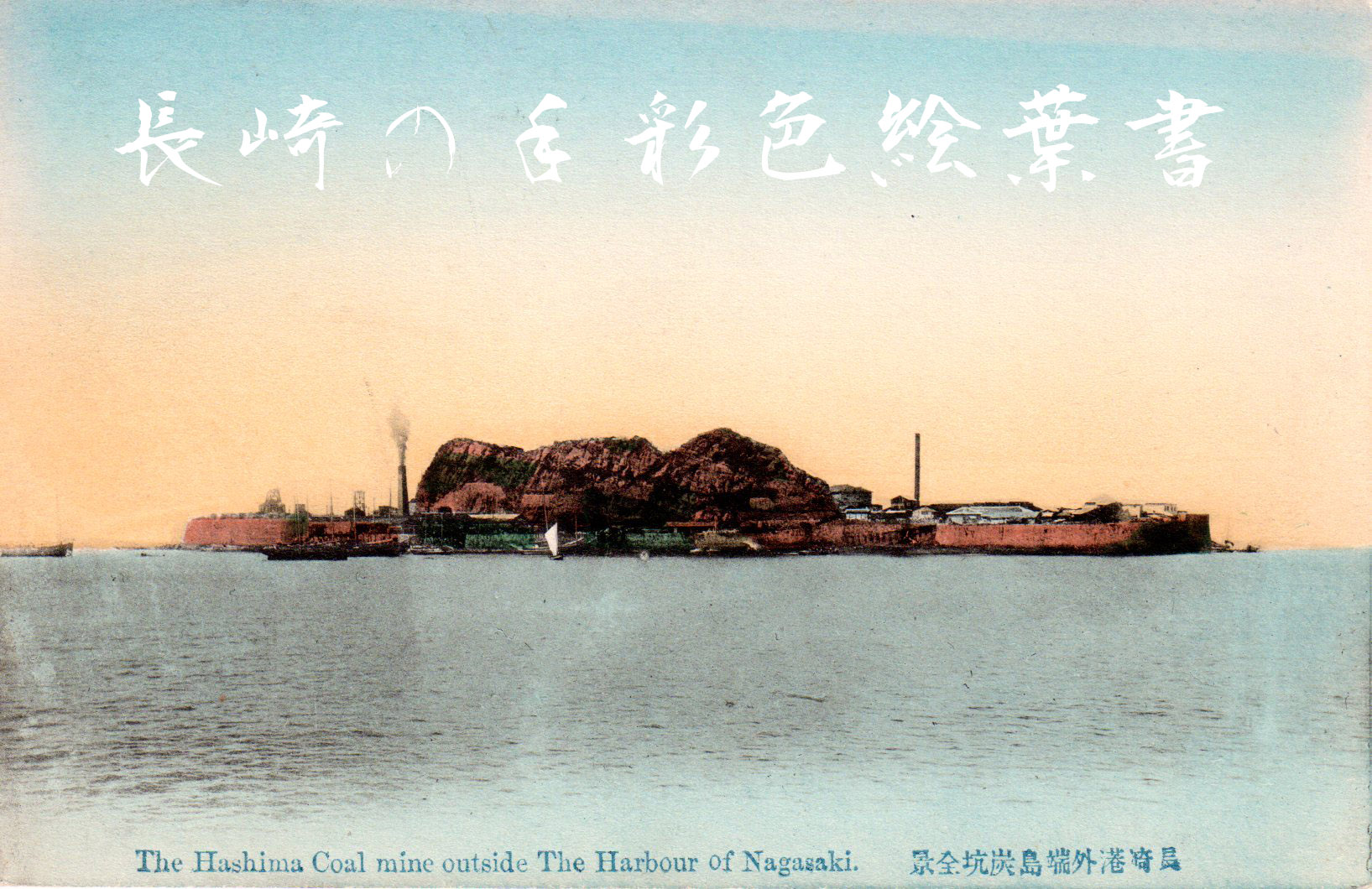

The Hashima Coal Mine outside The Harbour of Nagasaki

A hand-tinted Meiji-era postcard (c. 1910) showing Hashima Island viewed from the sea. Even at this early stage, the island's identity was being constructed through commercial imagery that emphasized industrial achievement.

Meiji-era hand-tinted postcard, c. 1910. Public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

This is the context in which celebratory imagery, including early commercial postcards and corporate publicity, acquires analytic weight. Such images foreground smokestacks, modern amenities, and bustling community life. They document real achievements, including medical facilities and robust public services. They also model a public language for the island that treats industrial modernity as self-explanatory, inviting admiration without demanding questions about how labor was recruited, disciplined, and differentially valued. The absences in these images are not simply missing facts. They are early evidence of how industrial spaces are narratively stabilized as heritage before anyone uses the word heritage.

2. Wartime Labor Mobilization (1939–1945)

Hashima's most contested history is inseparable from imperial mobilization in the Asia-Pacific War. From the late 1930s, Japan expanded legal and administrative mechanisms for directing labor to strategic industries, including mining. Coal was a war resource, and the demand to sustain output intensified the extraction of labor under conditions that normalized coercion across the empire. Historical scholarship and survivor testimony have documented the presence of Korean and Chinese workers at sites within Japan's wartime industrial system, including Hashima, and have described discriminatory treatment, harsh underground labor, malnutrition, violence, and elevated mortality.

For this learning resource, the key point is not only that coercion occurred, but that the wartime years are routinely made difficult to hold in view within public interpretation. A visitor can be invited to appreciate engineering ingenuity, community order, and the drama of undersea shafts without being brought into contact with the colonial conditions that made wartime production possible. This is the first place where "silence" should be understood as a mechanism rather than a gap. When contested histories are acknowledged only as fleeting reference, framed as controversy rather than as historical responsibility, or displaced into the language of "balance," institutions can appear to include everything while operationally limiting what becomes sayable.

Scholarly Context: Procedural Containment of Difficult Pasts

Kim and Gordon's procedural lens helps here because it clarifies why this thinning can be reproduced even when disagreement is publicly acknowledged. When institutions learn to treat difficult pasts as matters for "dialogue," "consultation," or "appropriate phrasing," the practical outcome can be indefinite postponement without formal refusal, and a steady relocation of the problem from history as evidence to history as reputational exposure (Kim and Gordon 2025). For Hashima, that relocation is precisely what later heritage governance makes easier to sustain.

Placing wartime labor at the center of Hashima's history is analytically necessary, but it also requires a disciplined sense of scale. The island was one node within a far larger imperial labor regime whose coercive force operated through law, recruitment channels, policing, confinement, wage discipline, and radically unequal exit options, and whose effects were unevenly distributed across bodies marked by colonial status.

For public interpretation, however, that scalar complexity often gets flattened into a binary dispute about terminology, as if the problem were merely what to call labor rather than how to understand a system that converted colonial subjection into extractive capacity. This flattening matters because it enables an institutional stance in which "controversy" becomes the primary object of management. A site can acknowledge that the 1940s are sensitive while treating sensitivity as a reason to minimize salience, to relocate the issue into supplementary materials, or to reframe it as a matter of competing perspectives that must be balanced. That repertoire is precisely the sort of procedural containment Kim and Gordon highlight in UNESCO-centered memory politics, where the practical work is often less about adjudicating evidence than about routing conflict into processes that delay or dilute responsibility (Kim and Gordon 2025).

3. Decline, Abandonment, and Ruin (1945–2000s)

After 1945 Hashima continued as an operating mine under transformed political conditions, but its underlying logic as a concentrated, corporate-managed industrial environment persisted. The island's population peaked in 1959, when housing, schooling, medical services, and provisioning were calibrated to sustain a dense community in a hostile marine setting. Then the national energy regime shifted. As Japan moved from coal to oil, the mine's economics became untenable. Mitsubishi closed operations in January 1974, and residents departed rapidly. What remained on the island was an accidental archive of everyday life: furniture, desks, appliances, and signage caught in the speed of exit, alongside industrial infrastructure built for permanence and then abandoned.

Hashima Island Today

The abandoned island off the coast of Nagasaki. The concrete high-rises that once housed over 5,000 people now deteriorate within the seawalls that define the island's artificial perimeter. This is the image that dominates contemporary representation — the photogenic ruin, stripped of historical context.

Photo: Shutterstock (ID: 140744941). Used under license.

Over subsequent decades, salt corrosion and typhoons turned the island into a modern ruin. The same reinforced concrete that once symbolized durability became an aesthetic of decay. "Battleship Island" became a name that travels easily in tourism promotion and popular media, and the ruin image now dominates visual circulation of the site. This aesthetic is not politically neutral. Ruins invite contemplation of impermanence and technological hubris, and they can be ethically seductive because they encourage a form of looking that treats history as atmosphere. The viewer can mourn abandonment without confronting wartime coercion, colonial hierarchy, or the unequal distribution of risk and suffering.

Here time becomes a political instrument. The ruin aesthetic pulls attention toward the late 1950s and 1970s, toward peak community life and sudden exit, while allowing the 1940s to recede. That temporal staging is one reason why high-fidelity reconstructions, whether photographic, cinematic, or interactive, can coexist with historical silence. Silence can be produced by what a narrative lingers on, not only by what it omits.

Why the Postwar "Golden Age" Matters for Heritage

The postwar decades also help explain why the island's later ruin image became such a powerful mnemonic. Hashima's peak community years generated an archive of affect, photos of schools and festivals, stories of children playing on rooftops, and memories of dense neighborliness that can be narrated sincerely without reference to the coercive histories embedded in the mine's earlier labor regimes.

When the mine closed in 1974 and residents departed quickly, leaving behind domestic objects that later became icons of abandonment, the island effectively supplied heritage entrepreneurs with ready-made scenes of "everyday life interrupted." Over time, that interruption became a portable narrative that travels well in tourism and media: it offers poignancy, the melancholy of modernity's obsolescence, and the aesthetic pleasure of decay. What it does not require is a confrontation with imperial governance or colonial hierarchy.

The 1974 break functions, then, as a powerful temporal hinge that can be made to stand in for history itself, allowing the story to begin in peak community and end in sudden departure, with wartime mobilization relegated to the margins as if it were an interpretive option rather than a constitutive condition.

4. UNESCO Inscription and Contested Memory (2015–Present)

Hashima's current interpretive landscape is inseparable from UNESCO World Heritage governance. In 2015, Japan secured inscription of the serial property "Sites of Japan's Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining." The listing process also formalized an international dispute over wartime labor. In that context, Japan acknowledged that "a large number of Koreans and others" were "brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions" at certain component sites and committed to interpretive measures enabling visitors to understand the "full history" (UNESCO World Heritage Committee 2015).

Tourism and Managed Access: Landing on Hashima, 2010

Visitors cross the purpose-built gangway to land on Hashima Island shortly after it reopened to tourists in 2009. This managed access — less than 5% of the island is open to visitors — shapes what can be seen and experienced.

Photo: At (Wikimedia Commons), August 2010. Public domain.

Since then, the dispute has been institutionalized as an interpretive compliance problem rather than a purely historiographical disagreement. UNESCO monitoring and Committee decisions have repeatedly returned to whether interpretive strategies, including institutional exhibitions and related informational measures, allow understanding of coerced labor and whether "appropriate measures to remember the victims" are present. In 2021, following a UNESCO/ICOMOS mission concerning the Industrial Heritage Information Centre, the World Heritage Committee expressed "strong regret" that relevant decisions had not yet been fully implemented and requested that Japan take the mission's conclusions into account (UNESCO World Heritage Committee 2021; UNESCO and ICOMOS 2021).

For this learning resource, the point is not to adjudicate every institutional claim. It is to clarify the environment in which any public representation of Hashima now operates. UNESCO decisions do not directly regulate private or university-based XR projects. Yet they shape reputational risk calculations, acceptable vocabularies, and institutional incentives around "balance," controversy, and liability.

Scholarly Context: How UNESCO Monitoring Shapes Local Heritage Practice

Kim and Gordon's contribution is to underline how UNESCO's multiple memory-related programs generate not only condemnations or endorsements, but also procedural "solutions" that can stabilize deferral as an outcome, and that stabilization travels outward, into local partnerships, museums, and media economies, as a practical sense of what is safer to show (Kim and Gordon 2025).

UNESCO inscription did not simply internationalize Hashima's visibility. It reorganized the site's historical temporality by attaching a global heritage framework to a place whose most politically charged histories fall outside the celebratory Meiji-centered narrative of "industrial revolution." The World Heritage Committee's 2015 decision, including Japan's acknowledgment regarding people "brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions," created an enduring interpretive obligation that persists regardless of local preferences (UNESCO World Heritage Committee 2015).

The 2021 "strong regret" decision, issued after the UNESCO/ICOMOS mission to the Industrial Heritage Information Centre, shows how that obligation can be translated into a compliance sequence, requests for reporting, and language of implementation that keeps the dispute active as governance rather than letting it settle as mere "difference of views" (UNESCO World Heritage Committee 2021; UNESCO and ICOMOS 2021). This is the environment into which any public-facing digital representation enters. Even when a project is not formally tied to UNESCO, institutional actors can experience interpretive choices as reputational exposure within a monitored field, encouraging cautious phrasing, de-emphasis, and procedural deferral as practical strategies for managing a conflict that is understood to be durable.

5. Extended Reality (XR) Technologies and the Public Mediation of Difficult Pasts

Extended Reality (XR) is an umbrella term that includes virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR). In cultural heritage, XR is often justified as a tool for access. It can simulate spaces that are physically dangerous, restricted, or no longer intact, and it can offer visitors a sense of presence and agency that conventional exhibition formats cannot easily reproduce. The same features that make XR attractive, however, intensify the ethical stakes of representing difficult pasts. When an experience feels immersive, the user's confidence in what is being shown can increase even when the representation is selective, and the design of what users can do, where they can go, and what the system treats as actionable becomes a quiet form of interpretation.

This is not an argument against XR. It is an argument for treating XR as public mediation rather than as neutral display. XR systems typically rely on production pipelines that include asset creation, scene design, review and QA cycles, platform constraints, licensing of imagery and sound, and institutional approvals for release. Each of these stages can become a governance surface. In heritage settings, these surfaces often reward visually convincing reconstruction while discouraging interpretive confrontation, particularly where a past is politically contested or legally sensitive. A useful baseline here is Innocente et al.'s review of headset-based XR in cultural heritage, which emphasizes that immersion, sense of presence, and perceived agency are core to the medium's appeal while also foregrounding unresolved design and implementation issues that shape what can be effectively communicated (Innocente et al. 2023).

Survey: Existing Hashima XR Projects

Hashima has already attracted substantial XR development, and the range of existing projects illustrates both the medium's possibilities and its characteristic silences. Google Street View captured 360° imagery of the island in 2013, enabling virtual navigation of areas beyond the tourist path; the same year, designer Bryan James released Hashima Island: A Forgotten World, an interactive web experience overlaying Street View with historical context and guided storytelling.

The Gunkanjima Digital Museum in Nagasaki, operated by a landing tour company, has since 2015 offered VR headset experiences, projection mapping, and—from 2024—a five-sided immersive LED theatre, all marketed as enabling visitors to access "restricted zones" unavailable on physical tours. Academic preservation projects, including Nagasaki University's Gunkanjima 3D Project, have produced photogrammetric models for heritage documentation, while independent developers have created everything from a 1:1 reconstruction of the island within the social VR platform VRChat to a commercial walking simulator on Steam inviting players to photograph the ruins.

What unites these otherwise diverse projects is a shared temporal orientation: they consistently foreground either the "golden age" of Showa-era community life or the photogenic decay of the contemporary ruins, while the wartime 1940s remain interpretively absent. The question is not whether XR can technically represent coerced labour—it can—but whether the production conditions, institutional partnerships, and audience expectations that shape these projects create systematic pressure toward safer, more atmospheric framings.

Those tradeoffs matter most when the past is difficult, because the ethical burden is not only accuracy of objects and architecture, but the intelligibility of violence, labor regimes, and unequal vulnerability. A faithful-looking mine shaft that cannot name coercive labor regimes, or that treats exploitation as ambient hardship, does not merely omit information. It participates in a public settlement of meaning. This is why, in later modules, the unreleased HashimaXR project will be approached as a governance problem rather than a product story. The central question is how procedural conditions, partnership expectations, and rights regimes can shape what becomes narratable in immersive form, including by halting development before contested history becomes publicly playable.

XR and the Risk of "Evidentiary" Space

XR's promise of access also carries a historiographical risk that is easy to underestimate: it can make space feel evidentiary. When users can "walk" through a reconstructed stairwell, classroom, or apartment corridor, the sensory confidence produced by coherence of texture, light, and spatial scale can be misrecognized as historical completeness, even when the experience is interpretively thin.

This is a familiar problem in public history, but XR intensifies it because design choices about movement, interactability, and narrative triggering operate beneath the threshold of explicit argument. An experience can guide users toward admiration, nostalgia, or melancholy through pacing and affordances alone, while leaving labor regimes and colonial relations as optional metadata, an "about" page rather than an embodied constraint.

Framework work on immersive XR in cultural heritage repeatedly returns to this tension between perceived presence and what can actually be communicated within the medium's practical constraints, a tension that becomes ethically acute when the past at issue involves coercion and unequal vulnerability (Innocente et al. 2023). The relevant question for our module, then, is not whether XR can represent difficult pasts in principle, but where, in the production pipeline, difficult pasts become vulnerable to being softened into atmosphere.

6. What Is at Stake

Hashima is not simply a historical site. It is an active arena of memory politics where industrial achievement, colonial violence, national identity, and international accountability are negotiated through infrastructure: official interpretation, tourism promotion, museums, and digital products. That negotiation is rarely expressed as an explicit denial. More often it appears as a managed distribution of emphasis. Engineering innovation is foregrounded, coerced labor is acknowledged in minimal or contested terms, responsibility is reframed as debate, and memorialization is displaced by claims of neutrality.

Digital representation amplifies these tendencies. High-fidelity reconstructions can make the island present, even intimate, while keeping the hardest histories procedurally out of frame. Because immersive realism can compress critical distance, it can turn a selective narrative into a felt certainty. This is precisely why an unreleased XR project can matter historically even before one narrates its internal development. If a project attempted to make space for historiographical conflict and coerced labor within an immersive environment, then the question of why it did not reach public release becomes a question about governance, partnership conditions, and disclosure discipline, not merely technical failure or ordinary attrition.

The next modules build from this case by explaining how heritage functions as an authorized practice, and why "silence" in digital heritage is often produced through workflow and institutional conditions rather than through overt narrative prohibition.

Scholarly Context: Memory Politics as Distributed Ecology

Kim and Gordon's larger point about UNESCO is helpful here as a framing constraint: when memory conflicts are increasingly governed through procedures that permit deferral and limit institutional exposure, the most consequential "decisions" may be the ones that never appear as decisions, but as routinized non-endorsement, endlessly pending review, and the steady narrowing of what collaborators treat as feasible (Kim and Gordon 2025).

Because Hashima is now mediated through multiple institutions at once, municipal offices, tourism operators, museums, UNESCO reporting structures, and a proliferating field of digital products, "memory politics" should be understood as a distributed ecology rather than a contest between two national positions alone. In such ecologies, the most consequential outcomes often emerge from ordinary-seeming decisions about emphasis, venue, licensing, and the acceptable time to address a contentious issue, decisions that can be framed as prudent stewardship rather than as interpretive exclusion.

This is where our case study of HashimaXR becomes analytically productive. A project can achieve high material fidelity and still fail to become a public argument if partnership conditions, rights regimes, and reputational-risk calculations align to favor detachable "assets" over historically explicit narration. Put differently, silence is not merely a gap in content. It is a patterned result of governance, one that can be produced by polite non-endorsement, by indefinite review, or by the steady narrowing of what stakeholders treat as feasible. Kim and Gordon's emphasis on procedure as a central arena of memory conflict helps us name that pattern without collapsing it into psychology or moralizing, and it sharpens our central claim for the module: in contested heritage, institutional time is itself a medium of interpretation (Kim and Gordon 2025).

Key Takeaways

- Hashima's engineered density made corporate governance and labor management inseparable from architecture and everyday life.

- Wartime coerced labor is the pivot that turns Hashima from an industrial success story into a site of international accountability and contested memory.

- The ruin aesthetic stages time in ways that can leap over the 1940s, converting historical responsibility into atmosphere.

- Since 2015, UNESCO monitoring has framed the dispute as an interpretive governance problem, with explicit expectations about recognizing victims and enabling understanding of the "full history."

- XR can increase access and presence, but it also intensifies the stakes of selection, because what feels "real" can remain interpretively silent.

References

Dionisio, Agnese. 2023. "Memories of Bathtubs and Apples: Touring the Industrial Heritage Information Center, Tokyo." The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 21 (7), no. 3 (December 21). https://apjjf.org/2023/21/7/Agnese-Dionisio/5782.

Innocente, Chiara, Luca Ulrich, Sandro Moos, and Enrico Vezzetti. 2023. "A Framework Study on the Use of Immersive XR Technologies in the Cultural Heritage Domain." Journal of Cultural Heritage 62 (July–August): 268–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2023.06.001.

Johnsen, Nikolai. 2021. "Katō Kōko's Meiji Industrial Revolution: Forgetting Forced Labour to Celebrate Japan's World Heritage Sites." The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 19 (23), no. 6 (December 1). https://apjjf.org/2021/23/Johnsen.

Kim, Jihon, and Andrew D. Gordon. 2025. "Changing Politics of East Asian Colonial and Wartime Memory in UNESCO." International Journal of Asian Studies 23 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479591425000063.

UNESCO and ICOMOS. 2021. "Report on the UNESCO/ICOMOS Mission to the Industrial Heritage Information Centre Related to the World Heritage Property 'Sites of Japan's Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining' (Japan) (C 1484), 7 to 9 June 2021." https://whc.unesco.org/document/188249.

UNESCO World Heritage Committee. 2015. "Decision 39 COM 8B.14: Sites of Japan's Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining (Japan)." https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/6364/.

UNESCO World Heritage Committee. 2021. "Decision 44 COM 7B.30: Sites of Japan's Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining (Japan)." https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/7748/.

📝 Cite This Module

Gerteis, Christopher. "Module 01: Hashima in Time and Place." HashimaXR Learning Resource. SOAS University of London, 2025–2026. https://hashimaxr.netlify.app/learn/module-01/.

For other formats, see How to Cite · Full Bibliography